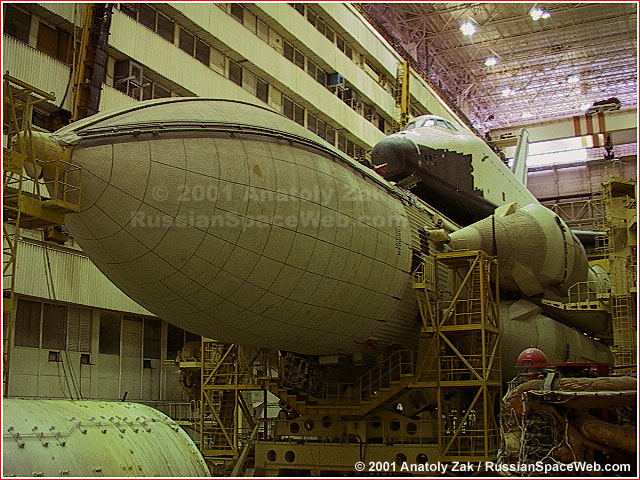

In fact, you could say the Soviet spaceplane, which reached Earth orbit just once in 1988 and never returned to space, succeeded beyond all expectations and failed dismally-both on the same day. vehicle for no reason other than to keep up with the competition.īut seen another way, Buran was an impressive technical accomplishment. It became for them the perfect symbol of a space program that had lost so much confidence that, at the behest of the Soviet military, it copied a U.S. Pilots, scientists, engineers, and the technicians who built the vehicle all speak candidly, if a little diffidently, about what they see as a sophisticated, spectacular failure. Like most Russians who worked on the Buran, Zabolotsky is still indignant about the experience. So the Buran may have kept me alive, and it helped my daughter find a career with a future.” “And after what she observed-my distrust of the bosses and the way they treated me-she declined to join the cosmonaut corps. “My daughter, Margarita, was recruited to be a cosmonaut,” he continues. Before and after his years training for the Buran, Zabolotsky flew more than 70 kinds of aircraft. “We lose three or four test pilots every year, so wasting all that time probably helped me survive that career,” Zabolotsky says wryly. In the early hours of 15 November 1988 at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan this was finally put to the test with what would become the only flight of Buran.WHEN VICTOR ZABOLOTSKY, A TEST PILOT WHO ONCE TRAINED TO FLY the Soviet Buran space shuttle, thinks back on the project that dominated his working life for nearly a decade, he figures some good came of it despite Buran’s cancellation. The biggest difference, however (and another way in which the Soviets had the upper hand), was the capability of the Buran to be launched, flown, and landed completely remotely. Because of this, the Buran was deemed just another payload for the Energia rocket. It could work independently to launch up to 100 tons into low-Earth orbit – a huge advantage over the American’s 30 ton limit. Energia was a heavy launch system in its own right, composed of a huge central four-stage rocket with four strap-on boosters attached to its sides. Instead it relied entirely on the Energia rocket to get it into orbit. Unlike the American Shuttle, the Buran shuttle wasn’t fitted with powerful heavy lifting boosters at its rear. The Buran shuttle had a forward crew cabin with six workstations and is almost the same length as the Space Shuttle with a payload bay (fitted with two robotic arms), wings, and fins identical in size and layout.īut one big difference was the way that these two shuttles were launched. Like its American counterpart Buran was composed of a reusable spacecraft attached to the side of a huge rocket. In 1980, one year before the first flight of NASA’s Space Shuttle, the Soviets began to construct their own shuttle system which they named Buran, which loosely translates to “Snowstorm on the Steppes”.Īt a glance, it’s clear just how similar Buran and the Space Shuttle really were.

Over the next few years they began to gather information about the Space Shuttle, using agents of the KGB (the Soviet secret service) to hack into the databases of American universities. There was an initial reluctance to design a spacecraft so similar to the American Space Shuttle, but after extensive wind tunnel tests, Soviet engineers couldn’t help but agree that the US design was ideal. Undeterred by their failed N1 Moon rocket, in 1974 the Soviet space agency began their own shuttle programme.

Matching the Americans’ capabilities was as critical as it had ever been. What could the Americans need with so many potential launches and so much cargo? There were fears amongst the Soviet military that the Shuttle could launch laser weaponry that could knock out nuclear missiles during flight, be used to construct a military base in space, or even be used to dive bomb Moscow from orbit. Capable of launching 30 tons of equipment into space and of being launched up to 50 times in a single year, the military capabilities of this new American shuttle were not lost on the Soviets. In 1981, after years of testing, NASA launched Space Shuttle Columbia, the world’s first space shuttle flight. With these sorts of craft, spaceflights could become more regular and costs could be kept down. For some time both the Americans and Soviets had been planning the development of a reusable spacecraft to be used for missions to low-earth orbit.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)